Sources and Bibliography

This narrative draws from well established historical research, regional archives, and interpretive writing related to Butch Cassidy, Browns Park, and outlaw life in the closing years of the American West.

Museum of Northwest Colorado

Archival materials and regional historical interpretation related to Browns Park, outlaw routes, and frontier life in Northwest Colorado.

https://www.museumnorthwestco.org/

Colorado Encyclopedia

Biographical and regional entries on Butch Cassidy, Browns Park, and Western outlaw history.

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/butch-cassidy

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/browns-park

Utah State Historical Society

Contextual research on Robert LeRoy Parker, early outlaw culture, and regional settlement patterns.

https://history.utah.gov/

Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection

Frontier era newspaper reporting on train robberies, manhunts, and public perception of outlaws.

https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/

Redford, Robert.

The Outlaw Trail. Grosset and Dunlap, New York.

Brown’s Park and the Vanishing West

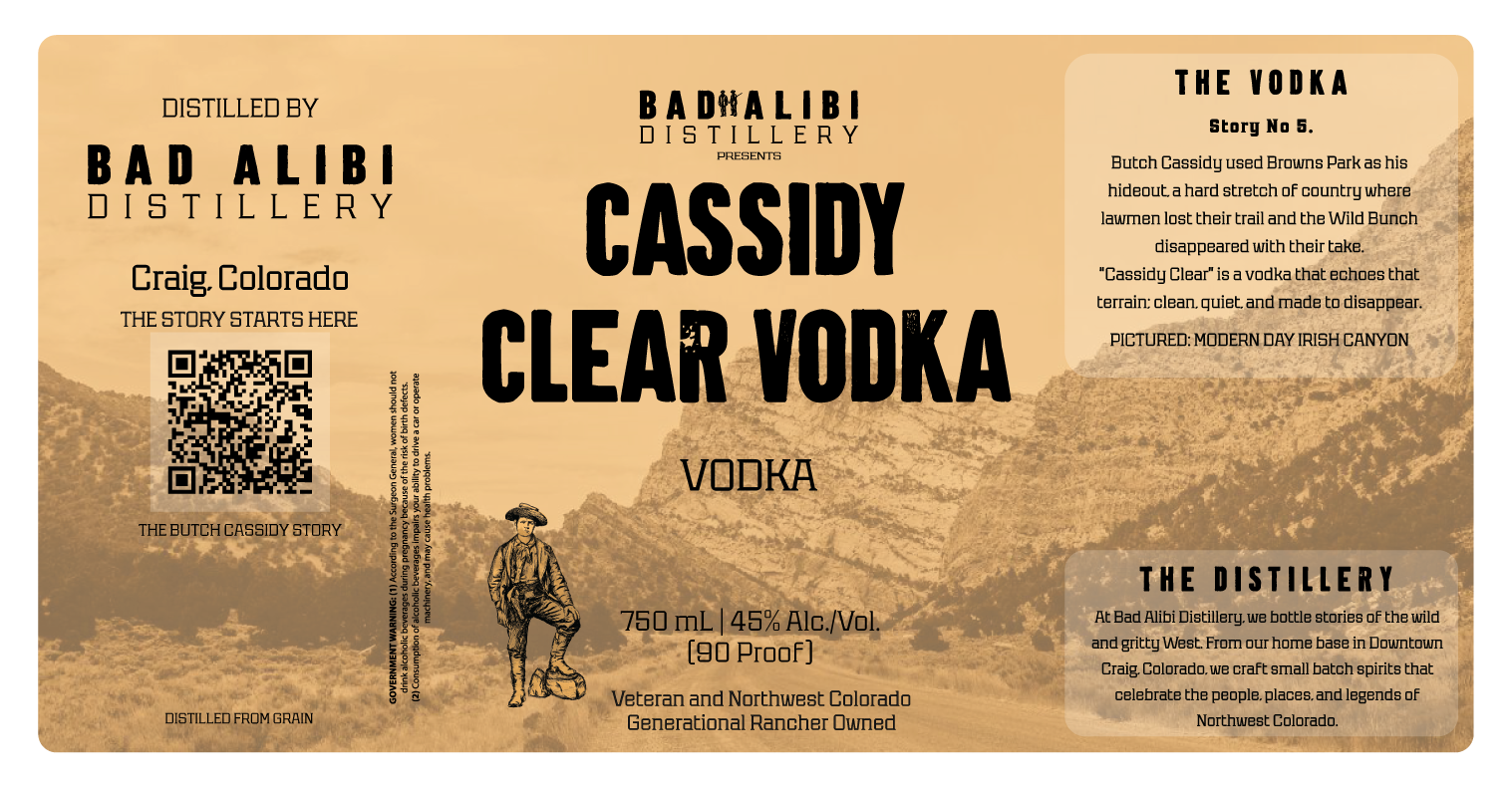

Robert LeRoy Parker became Butch Cassidy not because he set out to be famous, but because he was exceptionally good at disappearing.

Born in 1866, Parker grew up in a West that still allowed men to reinvent themselves, especially if they understood the land. By the time he began using the name Butch Cassidy, the open country of Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming was already tightening under the pressure of railroads, banks, and expanding law enforcement. What made Cassidy different from so many others was not violence or bravado, but restraint. He preferred planning over chaos, precision over force, and escape over confrontation.

Brown’s Park played a central role in that approach.

This remote stretch of country, tucked along the Green River and brushing against state lines, was a natural refuge. It was hard to reach, lightly governed, and well known to ranchers and riders who understood its hidden routes and seasonal rhythms. Cassidy used Browns Park not as a hideout in the dramatic sense, but as a place of regrouping. It was where plans were made, stolen horses were traded, and men could blend into the daily work of the valley without drawing attention.

Unlike many outlaws of his era, Cassidy avoided killing whenever possible. His robberies were deliberate and calculated, often targeting banks and trains associated with large corporate interests rather than individuals. He cultivated a reputation for courtesy during robberies, returning personal belongings, calming nervous clerks, and leaving without unnecessary harm. This approach did not make him lawful, but it did make him harder to demonize in the public imagination.

Over time, Cassidy became associated with the loosely connected group known as the Wild Bunch. They were not a formal gang so much as a shifting network of men who rode together when it suited them and separated just as easily. Their strength lay in coordination and movement, not territory. When pressure mounted in one place, they simply went elsewhere.

What ultimately set Cassidy apart was his refusal to cling to the past.

As the West closed in and manhunts intensified, he recognized what many others did not. The old ways were ending. The margins were shrinking. Rather than push toward a violent conclusion, Cassidy chose to leave. He vanished from the American West and reappeared in South America, where he attempted to start over, first as a rancher and later as an outlaw once again when financial reality set in.

Even his ending remains uncertain.

Accounts of his death in Bolivia have been debated for more than a century. Some insist he died in a shootout. Others believe he escaped yet again and quietly returned under another name. What is certain is that no confirmed body was ever brought home, and no ending ever fully closed the story.

That uncertainty is part of his legacy.

Cassidy Clear Vodka exists in that space. Clean, restrained, and intentionally smooth, it reflects a man who understood that survival often depended on knowing when to fade out rather than stand your ground. This is not a spirit built on spectacle or force. It is meant to move easily, to disappear without friction, and to leave only the faintest trace behind.

Butch Cassidy mastered the art of leaving before the door closed.

Cassidy Clear Vodka does the same.